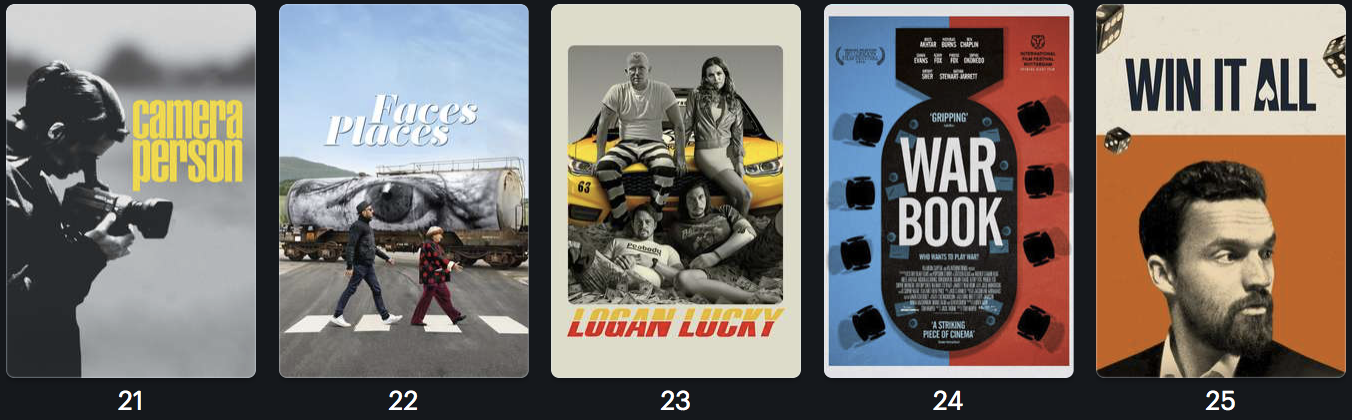

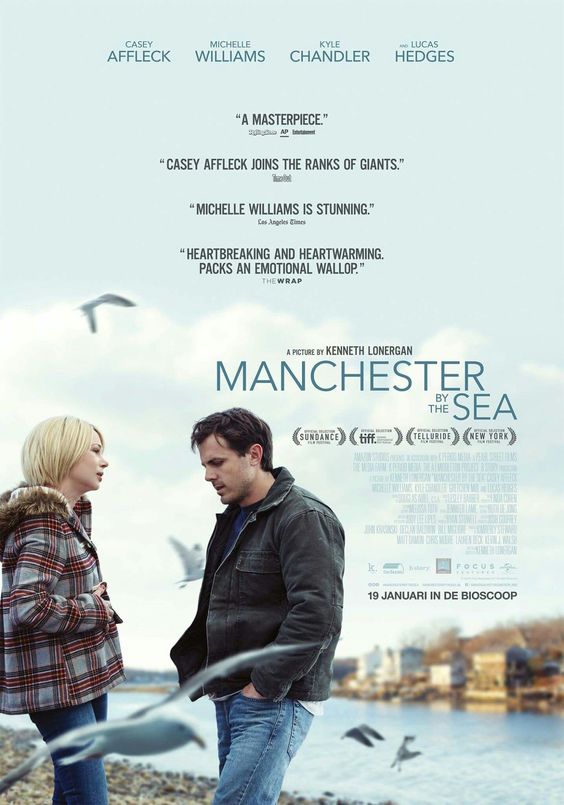

Greetings, Viscerals! I don't know about you, but 2017 has been a strange, confounding, educational year 'round these parts. Last year, we made a movie. (Well, mostly; the first quarter of this year was spent refining it and finishing it for good, but I digress...) Each stage of making a movie seems like the hardest; writing is like drawing blood, shooting left me physically wrecked and the 11 months of start-stop post-production seemed endless... so this year, it came time to send our baby out to film festivals and rattle tin in hand in search of distributors, sales agents and cinemas in order to release it. So believe me when I say that 2017 taught me -- as much to my surprise as anyone else's -- that this is the hardest part of independent, micro-budget, self-financed and/or crowdfunded filmmaking. We remain optimistic that we'll find a home somewhere, but I won't lie to you: it's been tough. A certain amount of it was expected; Trench has an emerging cast and unknown filmmakers, is shot in black-and-white, framed in a 4:3 aspect ratio and pays homage to a long-dead genre (film noir), while flirting with a few others (comedy, thriller). Needless to say, we figured distribs and sales folk wouldn't be elbowing each other out of the way to throw cash and screens at us. However, we did expect to catch some film festival fire, and this is where our journey thus far has been most disappointing -- particularly as we've received such truly wonderful and encouraging responses to the film from distributors and sales agents who have turned us down. Industry folk are increasingly divided over the worth of film festivals. Naturally, a nod from one of the big ten (Cannes, Venice, Berlin, Locarno, Toronto, Telluride, Sundance, TriBeCa, etc) remains a golden ticket with the ability to open all sorts of doors, and a Fantastic Fest, SITGES or San Sebastian slot can propel a genre film to similar heights, but it's the thousands of others that lie at the heart of this division. Do laurels mean anything to distributors and audiences, particularly if they're from festivals nobody's ever heard of? Do they still provide a great opportunity to get your film seen or, with the proliferation of tiny festivals the world over, is the 30 or so people they might pull to a screening not worth the hundreds -- even thousands -- of dollars one may spend on entry fees (or sheer time hustling for waivers)? Is it more worth one's while to get your film on to iTunes or Netflix through an aggregator, pimp it yourself and try your luck to reach people all over the globe? These are the kinds of questions all microbudget indie feature filmmakers need to ask themselves now. The industry has changed irrevocably since all your heroes' origin stories occurred, and the pathways they took have, more often than not, been co-opted or paved over. It's certainly got us looking at alternative pathways, as we look to release Trench and prep the next picture. Yes, there absolutely will be a next Cinema Viscera picture, because we're just that crazy. (We're currently in the midst of writing it, so I've no further details to share right now.) But it's also been a rewarding year in many respects. Our last short film, Cigarette, screened to an excellent response at the Sydney Underground Film Festival, an event I've loved from afar and wanted to screen at for years. An earlier short film of ours, Scope, scored a surprise selection in the Los Angeles Neo-Noir Novel, Film and Script Festival, even being one of 15 nominees for Best Film! I received a promotion in my day-to-day job, something I've found much more enjoyable than I expected, and my work-life -- well, work-work -- balance is as good as it's ever been. I also celebrated the incredible (for me) milestone of 10 years of love and art with my favourite of all people -- the better half of my life and Cinema Viscera, Pez, aka Perri Cummings. (Here's to the rest of our days, Monkey Face.) I'm not going to get into the sociopolitical landscape of 2017 -- there are much better, more incisive and well-researched places to find those takes -- except to say that it seemed to consist of the first blows back against the rising tide of hate and prejudice that marked 2016. Sure, that stuff's not going away anytime soon -- and there were plenty of terrible decisions driven by greed, deeply upsetting tragedies and political culpability in human rights abuses -- but there were some encouraging signs here and there -- from the worldwide Women's March, to the French election of Emmanuel Macron over Marine Le Pen, to various US states agreeing to continue adhering to the Paris Accord (despite the White House's ridiculous decision to pull the nation out), to Australia finally voting Marriage Equality into law -- that we might have some chance in hell of starting to turn the tide. As for the world of cinema, with US studio blockbusters continuing to suck all the air out of the conversational room, was there a similar narrative at play? An African-American US$1.3 million indie with queer themes took out the Oscar for Best Picture -- well, only after the title of a bigger, whiter movie, a US$30 million musical (and, it must be said, another indie itself), was read out incorrectly. Blumhouse, the horror mini-studio with the big-studio distribution deal, was the talk of the first half of 2017, with its under-US$10m hits, Shyamalan comeback Split and zeitgeist-buster Get Out, making huge profits as more traditional studios' efforts collapsed around them. Edgar Wright's idiosyncratic vision Baby Driver zoomed to success as Tom Cruise, Alien, Dwayne Johnson and Will Ferrell's new efforts couldn't get into gear, and a woman of wonders beat all comers at the summer box office in North America. Maybe a change really is coming... How did I find the year in film? Stay tuned, constant reader... PAUL ANTHONY NELSON'S UNEARTHED TREASURES OF 2017 Other than my personal and professional resolutions for 2018 -- to shoot our second feature, get our first feature released and travel overseas for the first time in my life -- I think I'd like to watch more old movies. The new stuff has been pretty good-to-poor, whereas my dips into the past have uncovered a wealth of gold. The 'Pioneering Women' program strand at the Melbourne International Film Festival was my unquestioned highlight of the fest, and provided two of my ten favourite discoveries of the year -- the first, ranking at #10, was Tender Hooks, the sole film by the late writer-director Mary Callaghan, starring the luminescent Jo Kennedy (whose other film in the same strand, Gillian Armstrong's ebullient musical Starstruck, also wasn't far away from this list). A ramshackle romance between two itinerant young Sydneysiders with refreshing realism and buckets of charm, Tender Hooks is living proof that Australia can make movies about people on the margins with humour and heart, not abject misery. At #9 is a film that eluded me for far too long: Abel Ferrara's mad, operatic NYC crime drama King of New York. Shot with Ferrara's usual misanthropic gaze with room for eccentricity and lashings of style, this tale of a crime boss aiming to close the past and secure his future as a different kind of city kingpin is a scathing, violent and often funny takedown of modern capitalist structures. Walken is in career-best form, but Laurence Fishburne steals the film right from under him. #8 was my top film of my now-annual 31-horror-films-in-31-days Halloween at home film festival Shocktoberfest: Michael Haneke's original Funny Games. I'd seen his shot-for-shot remake, which did prime me a little for this, but man, does the O.G. version still pack a punch. I don't completely agree with its thesis -- that our complicity in and demand for on-screen violence implicates us as monsters caving in to our base desires -- but it's a fascinating, thrilling take on it; one that also (and this is surely no accident, given Haneke's wartime Austrian upbringing) doubles as a microcosmic look at life under fascism. Haneke's one of the greatest filmmakers of our time, excoriating human foibles and social conventions through his unsparing, unblinking eye, but also, perhaps, the greatest thriller director we never had. Thanks to the Australian Centre for the Moving Image in Melbourne, we were given the opportunity to revisit ten classics by the Japanese master director Akira Kurosawa, handpicked by the doyen of Australian film critics, David Stratton. It was this retrospective that provided two of my 10 picks for this list -- the first, at #7, is Ran, Kurosawa's brilliant adaptation of Shakespeare's King Lear, transplanted to feudal Japan. As its final scene so eloquently states, Ran reveals a human race abandoned by gods and men, standing lost and alone, cursed with mutually assured destruction. At #6 stands a film that the Astor Theatre couldn't have programmed better for my birthday: Richard C. Serafian's counter-culture car-chase classic Vanishing Point. Thrilling chases and novelistic storytelling frame an absorbing outlaw tale, which ends up as a surprisingly powerful anti-establishment elegy, set amongst the early-'70s death throes of counterculture optimism. My fifth-favourite discovery of 2017 was also facilitated by ACMI, and also long-overdue: Andrzej Zulawski's Possession, a horror film about the destruction of a relationship, which is so confounding, and pitched at such a berserk intensity, that it somehow manages to dig up profound truths of love turned acidic, crumbling institutions and destructive obsessions... all with a rad Carlo Rimbaldi-created tentacled sex beast. Zulawski asks everything of Sam Neill and Isabelle Adjani, and then some -- the latter, in particular, delivers a stunning performance that feels like Marina Abramovic via Lars von Trier. Desire is a monster, yo. #4 is the second Kurosawa classic that floored me this year, the kidnap drama High and Low. Both a brilliant moral thriller of class division and as riveting a police procedural as you'll ever see, all superbly staged with breathless momentum, pitting Kurosawa's favorite megastars -- Toshiro Mifune and Tatsuya Nakadai -- head to head once again. Just the way Kurosawa blocks his actors in this thing should be taught in film schools. At #3 is the most buried treasure on this list, again thanks to MIFF's 'Pioneering Women' strand (thanks must go out to programmers Alexandra Heller-Nicholas and Michelle Carey for putting it together), a true lost classic of Australian cinema: Laurie McInnes' Broken Highway. Prestige, specialty or cult blu-ray companies, you're on notice: this is a title that absolutely should be on your radar for a 4K scan and release. Looking stunning on the big screen, in a pristine print courtesy of Australia's National Film and Sound Archive, Broken Highway is a truly hypnotic monochrome nightmare, set among a town of living ghosts, sucked dry and hollowed out by pathetic, destructive men. Not only does it star perhaps the quintessential early-'90s Australian cast (Aden Young, Claudia Karvan, David Field and, of course, Bill Hunter), it was also nominated for the Cannes Palme D'Or(!!), making its virtual disappearance doubly baffling. But here's the kicker: I wouldn't dream of using the Lord's name in breathless hyperbole, so let me be very clear how much I mean this... the filmmaking influence which McInnes' startling, emotionally bracing debut is most reminiscent of, is none other than David Lynch. The way she uses black-and-white film, textures, shadows, rusted-on eccentric behaviours, 1950s iconography, pauses -- in 1993, Laurie McInnes made the closest thing to a genuine Australian David Lynch film... and we seem to have collectively wiped it from our memory. So please: Arrow, Criterion, Eureka -- RELEASE THIS FILM IN RESPLENDENT BLU-RAY and give McInnes her due. Seeing this film on a big screen, being drawn into its web, left me physically trembling. Either one of my top 2 discoveries could be #1, so I'll just say they're my favourite documentary and feature discoveries of the year: Jennie Livingston's seminal 1990 doc Paris Is Burning and Norman Jewison's 1975 dystopian sci-fi/sports/action/thriller Rollerball. Paris Is Burning is a vital document of the then-fringe subculture of New York City drag balls, where gay people of colour could step from the mean streets, homophobia and the AIDS crisis of 1980s NYC and emerge into a wonderland where they could fully embrace their identities, and even rule, in a scene that has subsequently left us with a remarkable cultural impact -- everything from Madonna's 'Vogue' to terms like "realness" and "throwing shade" emerged from these clubs. By focusing on a number of performers, talking direct to camera, as well as capturing the fun, bold and often hilarious routines from the balls themselves, Livingston's lovely, remarkably intimate film -- which had me fully engrossed, even crying with laughter at times, but left me weeping inconsolably by the end -- remains a defiant, celebratory firecracker, even when it's haunted by tragedy. Perhaps the polar opposite to that in every way, Rollerball was the dystopian, anti-capitalist, scifi-sports-movie-action-thriller I never knew I needed. A compelling look at a future where hyper-free-market culture has won, and wars have been replaced with global, corporate-backed Rollerball tournaments between nations, the USA's star player is Jonathan A (played by James Caan, who absolutely convinces as this athletic beast, a blunt instrument of a man), who is savvy enough to realise he's a disposable commodity being exploited by a corrupt system, but isn't clever enough to outsmart it, until he realises that the qualities that make him a great Rollerballer may hold the key to his ultimate bid for freedom. Both a thoughtful dystopian sci-fi picture AND a bruising sports flick with truly mindblowing stunt and choreography work -- watch these Rollerball matches and try to work out how nobody was killed or injured -- Rollerball's view on the commodification of both sport and our humanity is all too depressingly prescient. Before we count off my favourite cinematic delights of 2017, allow me to direct you to... The real best film of 2017?When all is said and done, my favourite motion picture experience of the year wasn't even a film, in the traditional sense... nor was it a TV series in the traditional sense, given that even its creators made it as an "18 hour movie"... From its bizarre, disquieting first episode, Twin Peaks: The Return required a recalibration of how one watches TV or film -- hell, any kind of storytelling media -- as each languidly paced, darkly eccentric scene that unfolded was another step leading the viewer back into Lynch-land; that place where time is elastic, dreams and reality are one and your nightmares are hurtling down a highway at midnight, getting closer by the second. I am an unabashed, unashamed, unapologetic David Lynch fan -- my path with his work began as a strange and difficult one, as my emerging 18-25 year-old film buff brain found itself continually willing to grapple with his work, but finding my reactions to his films landing at all points of the emotional spectrum. Over the ensuing decades, every time I would revisit Lynch's films -- especially the ones I hated upon first viewing -- I got something more out of them; whether that be nuance, context or just plain terror. But in 2015, my friend Thomas Caldwell opted to discuss Lynch's career on the film podcast I used to co-host with Lee Zachariah, Hell is for Hyphenates, which led me on a deep dive back into Lynch-land... and it is here, watching every scrap of Lynch ephemera I could lay my hands on, that I would become a Lynch devotee forever more. As much as I love and trust Lynch and his writing/producing partner Mark Frost as artists, there was always a twinge of fear going into The Return. I'm not generally a fan of sequels, of going back to old, well-worn territory. But, as we know, the original Twin Peaks closed in the most existentially maddening way possible, in such a way that demanded some kind of resolution -- or at the very least, as Lynch-land is rarely a home to neat endings, some relief. After the first two episodes, all such fear had disappeared, and I was strapped in for the ride. Whatever dark path, odd floor-sweeping digression, city-halfway-across-the-nation-from-Twin-Peaks diversion or bonkers netherworld Lynch and Frost wanted to lead me down, I was right there with them. Oh, and then there was that time Chapter 8 came along and smashed my brain into a million tiny terrified pieces. I understand how absurdly long this blog post already is, so I won't go into all the things I loved about Twin Peaks: The Return. Let's just say I loved far, far more moments, performances, twists, meditations, metaphors and digressions than I didn't. I expected it to be bone-chillingly scary and hilariously funny, but what I didn't expect was how crushingly sad it could be -- especially seeing the world through the poor, addled, quite-literally-soul-searching gaze of dim Dougie Jones. Kyle MacLachlan's three-pronged performance in this show was continually a marvel to behold, and -- okay, this will sound like hyperbole, but screw it -- I feel that any TV acting award he doesn't win this year will be simply a fraudulent exercise in wasted praise. He's fucking spectacular in every frame: a shark in (barely) human skin as "Mr. C", a sweetly inquisitive child trapped in a body his flickering consciousness barely understands as Dougie, and when The Other Guy shows up, well... let's just say there were tears of joy. It even somehow gave us the resolution we wanted, in Chapter 16, and the lack of resolution we needed -- as well as a chilling reminder of cycles of abuse and the irreversible permanence of violent acts -- in Chapter 17. I could go on, but I should probably just write a post all about this show one day, once I've watched the entire thing again. Even with its occasional imperfections and willfully unresolved story threads, every episode of Twin Peaks: The Return was a delight -- not to mention the week-to-week experience of sharing it with the world in an age of isolated binge-watching -- as it represented the kind of huge-scale artistic vision made with such a total level of creative control that, in our increasingly corporate media landscape, we may rarely, if ever, see again -- and for this, alone, it should be valued. (Showtime deserve a ton of praise for making this happen, by the way.) So, to David Lynch and Mark Frost, I say: THANK YOU. Thank you for pushing televisual art to a new level, for this strange, wonderful, absurd beast of an "18-hour film" -- and for allowing television to dream again. Now... I reckon it's just about time we venture into the cinema, don't you? PAUL ANTHONY NELSON'S TOP 20 FILMS OF 2017 I almost feel unworthy of compiling a best-of list this year. I only saw 85 new movies this year, down from 97 last year -- the total seems to plummet annually -- and have missed many lauded titles; you won't find the likes of Call Me By Your Name, Blade Runner 2049, Thor: Ragnarok, Guardians of the Galaxy Vol.2, Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, The Shape of Water, Lady Bird, Okja, The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected), Wind River, Atomic Blonde, Detroit, Battle of the Sexes, Happy Death Day, The Square, Brigsby Bear, I, Tonya, American Made, Coco, Thelma, Phantom Thread, Downsizing, Wonderstruck, Mudbound and many more here, due to either my lack of time this year, or by virtue of them not being released in Australia as yet. One last thought before I count down: This might be the year that made me realise that, with ever fewer exceptions, I may finally be done with the modern blockbuster. From Wonder Woman to Justice League to Star Wars: The Last Jedi, more and more I'm finding the $100 million-plus franchise behemoth a frustrating, fundamentally compromised form of filmmaking, with the constant struggle of a filmmaker with a point of view mashing up against the tired tropes and expectations of the form, such as epic posturing and endless repetition, to very specifically cliched set-pieces and ideological box-ticking -- not to mention, egregious over-length in damn near every case. Only two of these kinds of films made my list this year; one, an unmistakable work of epic cinema from one of the last true mega-budget auteurs left, complete with a near-experimental structure and big stars blending in with unknowns; the other, almost an IOU note from a studio, rewarding a star for spearheading an entire franchise of 8 films over 17 years of huge grosses and critical goodwill -- by finally letting him off the leash to go full berserker. Without further ado... Honourable Mentions Jordan Peele's smashing social horror debut Get Out deservedly smashed the box office and gained plaudits as the first film to be seen to punch back against Trump's America; while hugely thrilling, I found the actual mechanics of its horror concept to have a few too many moving parts, diluting the scares, and it seemed to mix metaphors a bit, making it a little clunky at times, but holy crap, does it end spectacularly well -- that scene towards the end elicited perhaps the greatest cheer of relief I've ever experienced in a cinema. I look forward to seeing it again, and to see what Peele does next. I love me a great claustrophobic single-location thriller, and Clash delivers wildly on this count, as well as providing a terrifying glimpse -- based upon a real event -- of everyday life in a ideologically repressive, politically unstable region. The characters are well-drawn, the situation feels inescapably real, and it all leads to a horrifying conclusion. I've always been terrified of seeing Lav Diaz's films due to their off-puttingly excessive running times, but his latest one, The Woman Who Left, a tale of a wrongly imprisoned woman released after 30 years, who slowly plots her revenge on the person who put her there, sounded relatively accessible... and it came in just under four hours, rather than his usual five-to-seven. So I gave myself over to all 227 minutes of it, and was rewarded with a quietly riveting tale of vengeance and societal prisons, which unfolds like a meditative, contemplative TV series, shot beautifully in mournful monochrome. No-one does pass-aggress among the pretentious better than Alex Ross Perry. Despite being one of the few people somewhat disappointed with his last film, Queen of Earth, I found Golden Exits a welcome return to form. Perry's wicked writing is as arch as ever, but also witty and often achingly real. What's more, Mary Louise Parker, Lily Rabe, Chloë Sevigny, Analeigh Tipton and a surprising Emily Browning comprised damn near my favourite female cast of the year. I so badly wanted to find a spot for Darren Aronofsky's stunningly original, utterly bonkers passion project mother! in my top 20, but I still don't know if this bold, florid, often funny, but hugely overblown take on religion and fame holds all the way up. What it works superbly as, without question, is a two-hour anxiety attack -- particularly if having strangers over at your house terrifies you more than, say, killer clowns. Will definitely revisit this one, sooner rather than later. I'm a huge admirer of the searching, character-based films of Joe Swanberg, and his latest film, Win It All (as well as his series, Easy) shows his relocation to Netflix is working out just nicely. This comedy-drama about a compulsive gambler who gets tasked with minding thousands of dollars of off-the-grid cash which -- surprise! -- he gambles away and has to win back, distinguishes itself from similar-sounding films via Swanberg's sheer warmth and empathy for his characters, even as the plot tightens the screws, and the level of ownership his actors have over their characters, giving wonderfully relaxed performances (Jake Johnson has found a serious groove with Swanberg, making a potentially grating character a joy to follow). It's also gratifying to see how far Swanberg has developed as a visual storyteller. A film from 2014 making its low-key Australian premiere in this year's Human Rights and Arts Film Festival (a rare non-documentary screening for them -- more features, please), War Book is a thoroughly gripping, talky, mostly single-location thriller about a gaggle of low-level UK government aides drafted to play high-level government roles in a mock disaster situation. What begins as a bunch of bored bureaucrats going through a prescribed exercise soon becomes fiery, as they begin to embrace their mock roles (as PM, Foreign Secretary and so on), slinging ethical arguments and insults back and forth (and played by an excellent cast of UK character actors). With a keen eye on our fatal flaws, this sharply written and acted tale of mutually assured destruction is bracing, intelligent and claustrophobic, transcending its stagy, modest trappings. Steven Soderbergh's return to the big screen, Logan Lucky, is as laid-back, fun and low-key ambitious (in regards to his choice to self-distribute the film) as anything he's ever made. Playing as a charming hick riff on his OCEAN'S flicks, with more than a few hints of Looney Tunes (especially in the design and colour scheme of the film) and the Coens' more benign work, this is a rollicking return for this most implacable of auteurs. It struck me that everybody in this story had integrity and/or value and/or a hidden gift, and this struck me as an important statement to take away in today's divisive landscape. Can Agnes Varda please be all of our grandma? The irrepressible octogenarian auteur and French New Wave goddess keeps quitting movies but always finds a way back, unable to resist the impulse to document the everyday intrigue she sees around her. With her latest documentary, Faces Places, she's enlisted visual artist J.R. (known for his photography and collage work presenting everyday people as objets d'art themselves) to join her on an odyssey of interrogating art and images, throughout the French countryside. J.R. turns out to be a charming subject as well, and Varda's burgeoning friendship with him makes these two an irresistible dynamic duo, whose intelligence, optimism, warmth and sheer life remind us that, just maybe, the human race may not be so irredeemably awful after all. This latter point is also evidenced by Kristen Johnson's alternately lovely and confronting documentary memoir, Cameraperson. A veteran documentary cinematographer, Johnson's directorial debut consists of, essentially, B-roll from many of the films she's shot for others, fashioning an utterly intriguing mosaic of impressionistic micro-documentaries from both unused interview footage and the intimate, unguarded, unpolished, even accidental moments that happen when the camera is rolling before "action" and after "cut". Covering everything from child victims of war zones to family life in postwar Bosnia-Herzegovina, to a day in the life of Nigerian midwife to Johnson's own mother's battle with Alzheimer's Disease, through the sum of everything she has seen and experienced through her camera, we see Johnson's life, in some fashion, as she has. It's damn near humbling to behold. THE TOP 20  #20: PREVENGE Actor-writer Alice Lowe (Sightseers, Hot Fuzz) makes an impressive debut as writer-director-star with this gleefully mordant horror comedy, with the irresistible premise of a pregnant woman submitting to the voice of her murderous unborn daughter. Shot for less than £80,000 in just 11 days -- with Lowe starring and directing while seven months pregnant (this will seem less condescending once you see what she puts herself through on screen) -- Prevenge is a rough little wonder, with lots of laughs, some decent jolts and one hell of a satisfying character journey, establishing Lowe as a charismatic, clever voice to watch.  #19: PADDINGTON 2 As worthy and joyous a follow-up as the first film was disarmingly great, turning its focus to how open-heartedness might be a more direct path to changing ways than aggression; which, as prosaic as that may sound, seems almost therapeutic in today's combative climate. Director/co-writer Paul King (he of THE MIGHTY BOOSH) seems to have made a James Gunn-GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY-Marvel style connection with this series and Michael Bond's books, the little Peruvian bear providing the perfect vehicle for his gift for finding sweetness and humanity in anarchy (and Britishness). It's adorable as hell, with a couple of emotional wallops and a perfectly cast ensemble having a ball.  #18: DUNKIRK Not as ceaselessly urgent as anticipated, but Christopher Nolan's powerful, near-Eisensteinian use of IMAX image and montage (and *that* soundscape) crafts a bracing tribute to bravery, while also lamenting the need for such action. Unquestionably the best filmmaker working on epic budgets in this day and age, Nolan tells this harrowing true tale via an almost-experimental structure -- a week in some characters' lives, alongside a day in another situation, alongside an hour in others, all happening concurrently -- and, somehow, it makes perfect sense. With Dunkirk, the director delivers his shortest, tightest film since his debut, and -- one wouldn't be out of line arguing -- his most emotional, intelligent and thrilling yet. (Personally, I ride or die with Batman Begins, Inception and Memento, but this is closing on them fast.  #17: SOUTHWEST OF SALEM: THE STORY OF THE SAN ANTONIO FOUR Upsetting, rage-inducing document of four Latina lesbians falsely accused of gang-raping two girls, leading to a two-decade fight for exoneration. Incorporating home video footage of the women at the time it happened to intimate, gut-wrenching interviews with them today, as well as statements from defence and prosecution attorneys, director Deborah S. Ezquenazi's film methodically compiles an overwhelming defence of their innocence, not to mention a tragic indictment of rampant homophobia, '80s "satanic panic" and toxic masculinity. Despite an abrupt ending, this is a powerful, moving tale of injustice and resilience.  #16: THE BIG SICK A big warm hug of a film, with an admirable commitment to creating a central relationship of real, adult complexity, which never skimps on any dilemma -- every issue the couple have in this film feels earned and thorny, as if it'll take forever for them to dig their way out of. This is a testament to Kumail Nanjiani and Emily V. Gordon's smashing screenplay, which also explores cultural clashes with wit and charm. To be fair, it does meander at times and is a bit too long, but everything else -- the wonderful cast (especially Ray Romano and Holly Hunter), Nanjiani's developing stand-up routines, the screenwriters' (and director Michael Showalter, also no stranger to this environment) depiction of the stand-up comedy world -- is calibrated as perfectly as a modern romantic-comedy-drama can get.  #15: LOGAN From a franchise (two?) I'd long lost interest in, Hugh Jackman, director James Mangold and his co-writers Scott Frank and Michael Green somehow fashioned a film that, nine months on, has stuck as far and away the best studio blockbuster I saw in 2017. This fierce farewell to Wolverine and Professor X feels like Fox's gift to Jackman and Patrick Stewart for 17 years of fronting the hugely lucrative X-franchise; after making eight for us, you can do one for you. Logan gives Jackman's Wolvie the broken, ultra-violent, profane, melancholic -- but ultimately hopeful -- coda he deserves, whilst deftly layering in an all-too-real vision of a crumbling America inhospitable to anyone different; the opening scenes seem directly lifted from the opening pages of Trump's America. Sure, there are some clunky metaphors at play, but the execution of this feels classical and sincere in a way most films produced at this budget level don't. Lastly, the film introduces us to a gale-force talent in the form of young Dafne Keen, whose fiery X-23's relationship with Logan and Xavier gives this picture its gravity. The fact such heart and brutality, such nihilism and hope, exist side-by-side is pure Wolverine, a testament to Jackman's genuine affection for this character who made him a superstar, closing with a beautifully elegant shot that, I won't lie, made me teary.  #14: A CIAMBRA My partner in life and Cinema Viscera, Perri Cummings, is of proud Roma heritage, which means I'm always keen to check out any (all too rare) cinematic excursions into this unique, transient, but tight-knit and fiercely defiant culture. (I highly recommend checking out Laura Halilovic's 2014 comedy My Romantic Romani/Io Rom Romantica.) Based on his 2014 short of the same name, filmmaker Jonas Carpignano again looks at the same lead character, young Pio (Pio Amato, playing a fictionalised version of himself) as a likeable, clever, old-before-his-time Romani boy who bridges several cultural factions in his Calabria neighbourhood -- local Italians, African refugees and his Romani community -- which he navigates just fine, with an eye on emulating his older brother, until he's manipulated into a situation that will force him to choose a side, even if it means betraying a friend. Building upon his short films and his acclaimed debut feature Mediterranea (2015), Carpignano skillfully uses a modern neorealist approach and non-actors to craft a quietly heartbreaking tale of manhood and responsibility in a fringe Roma community.  #13: THAT'S NOT ME Full disclosure: I know the star-director-writing team who made this film a little bit. Well, I met actress Alice Foulcher at a party last year, where we spent ages swapping stories about the micro-budget films we were making (then met her husband, director Gregory Erdstein, after seeing the film, close to a year later). More disclosure: While Alice & Greg are lovely and funny, and the trailer for their film looked peppy... I wasn't sure it was my kinda thing. What's more: It got into the Big Melbourne Festival that I really, really wanted our film to get into. So it's fair to say I approached That's Not Me with mixed emotions... which made me delighted that I fell so hard for it. By a huge distance the best Australian indie I've seen in years, Foulcher and Erdstein managed to craft a debut so winningly assured, I could only feel a surge of pride and joy for what they'd achieved (even more so, on such a threadbare budget). Foulcher makes an alarmingly confident starring debut, but it's her and Erdstein's screenplay that's the real magic trick, mired in the uncomfortable truths of so many an aspiring Australian actor/filmmaker's experience. I can't recall an Australian film so casually charming, so bright and funny, which has also felt so genuinely honest and thoroughly lived-in. Can't wait to see what these two do next.  #12: CERTAIN WOMEN Kelly Reichardt has carved out a space in independent American film for creating small masterpieces of quiet desperation, but -- much as I admired Wendy and Lucy and Meek's Cutoff -- this is the first that really connected with me. Achingly precise, beautifully deliberate and everyday-poetic, featuring wonderful performances from Laura Dern, Michelle Williams, even Kristen Stewart and especially newcomer Lily Gladstone, Reichardt mines the short stories of Maile Meloy to dig into her characters' micro-struggles, continual concessions and prescribed roles, ultimately yielding heartbreak. (There are two unbroken shots of Gladstone towards the end of the film which will damn near bruise your soul -- and show why she should've been Oscar-nominated last year.) Really worth seeing on a big screen, if you can, where you can give yourself over to its gentle, wise cadences.  #11: MY LIFE AS A ZUCCHINI (aka MY LIFE AS A COURGETTE) See the poster to this film, right there? There's no way in hell I was going to see that movie. I don't generally connect with (non-Pixar, non-Brad Bird) animation, and cutesy stop-motion kiddie faces? Hell NO. Thankfully, in my previous job as a cinema usher, I was rostered on to a session, and the rapturous reviews I'd heard from friends made me pay attention. Wow. This poster is not the film I got... and yet? It also kind of is. Claude Barras' debut feature (based upon Gilles Paris' novel and co-scripted French indie darling Céline Sciamma, of Tomboy fame) is a gorgeous, often incredibly dark and, sometimes, even upsetting animated tale of kids orphaned and abandoned, told with disarming frankness, a huge heart and admirable brevity (65 minutes!!), with a cast of beautifully written characters who'll stay with you long after you've finished watching it. If you can't see it in French, never fear: the US voice cast is actually great. THE TOP 10 #10: IT'S ONLY THE END OF THE WORLD Anyone who knows me, uh, cinematically, knows I'm hook, line and sinker in the bag for Xavier Dolan. Every one of his films to date has a maturity, emotional rigor and confidence with both storytelling and the medium of cinema that belies Dolan's freakishly young age. Rather than hating on him out of pure jealousy, I've been powerless to deny the sheer ambition, curiosity and honesty of his films, culminating with the gobsmacking 2014 Cannes Jury Prize winner Mommy. So when It's Only The End of the World bypassed all forms of cinema release out here (save for a couple of French Film Festival screenings), sneaking onto home streaming service Stan, I had to worry: Had the Boy Wonder lost it? When I finally caught up with it, I was immediately engrossed. Why has this film been so marginalised? Not nearly as baroque as Mommy, Laurence Anyways or Tom At The Farm, this felt like a smaller, more theatrical chamber piece in between bigger movies (his US, English-language debut, The Death and Life of John F. Donavan is due in 2018), albeit starring an all-star dream team of French cinema: Marion Cotillard, Lea Seydoux, Vincent Cassel, Gaspard Ulliel and Nathalie Baye (who is amazing here). If I had any complaint at all, it would be that, at times, its stage origins do show (based, as it is, on a play by Jean-Luc Lagarce), but that'd be it; it deals with a combative, caustic family, but if that doesn't daunt you, jump right in: Dolan's surgical gift for dissecting flawed families see it soar, making this work as layered, affecting and propulsive as anything he's ever done.  #9: LUCKY When I saw this back in August, it was purely a joy to see Harry Dean Stanton play a star role again, some 30 years after Paris, Texas, but since his passing in November at the age of 91, it's a beautiful final chapter to one of the great American character acting careers. Actor John Carroll Lynch makes his directorial debut with this sweet, gentle, melancholy and amusing film, allowing Harry Dean to play a character very much informed by his own outlook -- he believes in "nothing", smokes cigarettes like they're disappearing, goes to the same bar every night and has a cheekily rambunctious streak a mile wide -- in a lovely look at mortality and freedom that's worthy of the great man. There's extra pleasure in seeing Stanton's old pal David Lynch in a rare acting role, playing an eccentric (you don't SAY) man obsessed with finding his escaped tortoise. In fact, Lucky feels all the world like Jim Jarmusch's Paterson at age 90 -- the two films seem connected by the same yearning, the same curiosity, the same satisfaction found in quiet lives lived authentically. RIP, Harry Dean -- hope you've got a guitar by your side and full deck of American Spirit at all times.  #8: FEBRUARY (aka THE BLACKCOAT'S DAUGHTER) While I admired its commitment to its odd, aggressively static aesthetic, I really hated Oz (son of Psycho's Anthony) Perkins' second feature, I Am The Pretty Thing Who Lives In The House... but there was enough of a vision at work there to compel me to seek out this, his oft-delayed first feature. Another film which deserved better than to quietly sneak on to home video and streaming service Stan, February (known in the US as The Blackcoat's Daughter) is the most genuinely creepy horror film I've seen from the 2010s. The simple setup sees two girls (Lucy Boynton and Mad Men's sad-eyed Sally Draper, Kiernan Shipka) left behind at a snowbound girls prep school as everyone else heads on a weekend break. As it turns out, one of the girls is incredibly, increasingly, weird. Meanwhile, another, older girl (Emma Roberts) is on a journey of her own through the winter night... Honestly, I've never seen such a whiplash 180 between first and second features since Richard Kelly's Donnie Darko and Southland Tales. Somehow, here, Perkins makes one of the all-time great horror debuts, gently crafting a chilling yarn of creeping malevolence and a little satanic-panic menace, employing unnerving sound design, stark visual control and his brother Elvis' wonderful score -- not to mention the special effect that is Kiernan Shipka, who is straight-up terrifying here -- to deliver an arrestingly cinematic creepfest that demands to be watched in the dark, turned up loud, on the biggest screen possible. I'll now wander down any dark path Oz Perkins deigns to take me.  #7: HAPPY END I think we can all agree that, regardless of whether his films appeal to you or not, Michael Haneke is one of the master filmmakers working today; the complete control evident in every frame of his glacial, jet-black, often score-free explorations of the worst aspects (or, best aspects in the face of mortality) of human nature is truly a wonder to behold. (Making a film, you become even more painfully aware of how difficult this level of control is.) For all of his formal rigor and moral exactitude, Haneke always struck me as the greatest thriller director we'll never have. Watching Haneke engage with genre is fascinating; his idea of horror film is Funny Games or Benny's Video, his take on a thriller is Hidden, his post-apocalyptic sci-fi/horror is Time of the Wolf -- all tower as unsparing, unblinking journeys into anti-genre. So, one may wonder, what would a Michael Haneke comedy play like? Thanks to Happy End, we no longer have to: true to form, he goes comic with a family album of bourgeois sociopaths, played brilliantly by Isabelle Huppert, Mathieu Kassovitz, Jean-Pierre Trintignant, Fantine Harduin, Franz Rogowski and Toby Jones. His look at a toxic, wealthy family in Calais struggling to communicate with everyday human emotions, slowly imploding in various ways, is as riveting as layered as anything he's ever done -- this family's dramas, by turns mordant, melodramatic and even murderous, play out as the mounting refugee crisis, barely glimpsed by this lot, plays out in the far background -- but adds an extra dose of casually caustic humour that works surprisingly well, leading to a double-show-stopper of an ending. At the age of 74, Haneke's work is as fresh and bracing as ever -- and, now, even funny.  #6: MOONLIGHT Barry Jenkins' Best Picture-winning triumph arrived under a hailstorm of hype, to the point where one's reaction to it felt like some kind of demand: you're with us or against us. The nature of online fervour felt a little out of control, and much too politicised, with the genuinely charming La La Land copping the brunt of a disproportionate backlash. So it's a testament to Moonlight that, even from beneath this suffocating hype, it manages to not only engage and impress, but leave a mark that stings, with images that stick fast. Using a seemingly endless array of cinematic elements at his disposal -- not just sensitive writing, intelligent direction and terrific actors (especially Mahershala Ali, Janelle Monae, Andre Holland and all three Chirons), but light, shade, texture and temperature -- Jenkins crafts an American original filled with pain, love, sensitivity and sensuality, more than worthy of his inspiration, Wong Kar Wai. A story of longing that isn't cloying, a story of desire that isn't indulgent, a boundlessly stylish film that never shows off or pokes you in the eye with it, it's a quietly powerful, surprisingly universal story that transcends some well-worn trappings to share an emotional, even profound, experience.  #5: THE KILLING OF A SACRED DEER In what seems to be a recurring theme in this year's list, I really didn't dig writer-director Yorgos Lanthimos' previous film, The Lobster, which felt like a great short stretched out to two laboriously strained deadpan hours to me. Turns out, the secret to Lanthimos making a genuinely great film was this: keep the idiosyncratic, dark-as-hell worldview, be a little less funny and even more horrifying. Bourgeois narcissism and seething sociopathy collide head on in Lanthimos coal-black morality tale, influenced by ancient Greek myth, embodied by a brilliant cast who are almost uniformily in career-best form (Farrell is brilliant, Barry Keoghan is something really special and I don't think I've ever loved a Nicole Kidman performance as much as this -- she is f-i-e-r-c-e). I won't go into story points or characters, as you should see this one as cold as possible. It may circle the drain longer than it should, but Lanthimos delivers a chilling, near-Kubrickian social horror film of diabolical proportions, which builds to one truly terrifying finale.  #4: IT COMES AT NIGHT I haven't seen Trey Edward Shults' debut feature, Krisha, but heard that it played domestic social-realist drama like horror, so I was interested to see what he did with an actual horror film. Beyond that, though, I had no idea what to expect -- and what I saw just floored me. It's a small, dark, intimate film with buckets of atmosphere, filled with terrific, naturalistic performances from its small but well-credentialed cast (Joel Edgerton, Carmen Egojo, Riley Keough, Christopher Abbott and Kelvin Harrison Jr). While its setup is very much that of the kind of post-apocalyptic, post-zombie-outbreak movies and shows we've seen, Shults' film goes to a completely different place, crawling under our skin by traversing this emotional terrain in a way I've rarely seen drawn this compellingly, economically or frighteningly. As the two families at its centre bond and form a micro-community in a world gone to hell, the insidious force that proves their undoing, that sees them baying for blood, is, more than any other... love. In this divided, fiercely protective, you're with us or against us age we currently live in, if that's not a heady, disquieting concept to keep you awake at night, I don't know what is.  #3: THE FLORIDA PROJECT Sean Baker manages to top his idiosyncratic, shot-on-iPhone indie wonder Tangerine in every conceivable way with this beautiful, big-hearted, social realist tale of kids and families (both real & makeshift) living in Florida's "welfare hotels", under the shadow of the capitalist mecca of nearby Walt Disney World. I'm generally dubious of stories told through the eyes of children, but the kid cast here is astonishing -- Brooklynn Prince as Moonee is so effortlessly natural, yet, somehow, enormously charismatic, and Valeria Cotto as red-headed Jancey just cracks your heart in two at all times, she's just adorable -- and Baker has a real feel for capturing kids doing the everyday stuff kids do, at how they create their own world within the one they've been saddled with. With his crew and wonderful cast of newcomers, non-actors and a lovely Willem Dafoe, Baker unearths everyday wonders, modes of survival and cycles of behaviour through a kind, unflinching, enormously empathetic lens. His characters are flawed, troubled, limited, abrasive, outcast, and yet, all seen with the utmost sense of love, openness and lack of judgement. The Florida Project is tragic, funny, truly social realist -- and exactly the kind of film I never knew I needed so badly.  #2: THE WORK This simply shot, straightforward documentary follows an intriguing proposition: Twice a year, California's Folsom State Prison opens up its doors to civilians, to observe and participate in their inmates' regular four-day group therapy sessions. We follow three men into the prison -- an African-American bartender confronting his lifelong fear of prison, a white hipster type looking for something but unsure what, and a swaggering Latin-American man looking to see how he "measures up" alongside hardened cons -- but as they discover, this isn't like any kind of group therapy session you've ever seen. Because these aren't just any convicts: they're "level four" prisoners -- murderers, rapists, notorious gang leaders, all inside for interminable stretches -- burdened with a seemingly insurmountable tonnage of emotional trauma, inherited toxic masculinity and psychological baggage to work through. As the sessions get underway, we see that these kind of patients employ a form of -- dare I say -- brutal sensitivity, as the cons shout, clutch, cajole, shove and scream their way through some dark, desolate, deeply wounded emotional landscapes. Along with the convicts, the three civilians we follow in also learn something confronting, primal, surprising and important about themselves. It's not an easy watch by any means -- the discussions are candid, profane, confronting and almost uncomfortably intimate -- but don't be misled: The Work is not a depressing dirge of wall-to-wall pain. In fact, watching the way these men reveal themselves, and have each other's backs (sometimes literally), is incredibly powerful to watch -- and, ultimately, important. Because this is the kind of rehabilitative experience our prison systems need to aspire to: Prisoners confronting their misdeeds, their guilt and their culpability, but also the people, influences and environments that led them there... and then using that knowledge to help others battle their demons. Undoubtedly one of the most heartbreaking, potent documentaries I've ever seen -- tears were streaming down my face just 30 minutes in -- Jairus McLeary and Gethin Aldous' film should be compulsory viewing -- particularly among men, young and old, who battle with the spectre of inherited, toxic behaviour every day: you don't have to give in to it. You can be better than that. You can confront it, confront yourself, and heal. You'll see even the baddest of badasses can cry... and that, more often than not, they're the ones who need to do so the most. ...which leaves us with my #1 release of 2017...#1: MANCHESTER BY THE SEA This film tore me in two. I didn't see it coming, but surprise was not the only factor -- just thinking about its small moments, its low-key confrontations, its emotional clarity, I know a second viewing would propel me to the same raw, uncontrollably tearful place. I'm not sure if it is just me getting older, or a reaction to the increasingly fraught world around us, or a reaction to the compromised, corporate-mandated and market-tested blockbuster cinema we're being fed year after year, but as 2017 went on, I started to discover that what I need most out of art these days is to be moved. Not in an overbearing, sentimental, not-a-dry-eye-in-the-house type way, but in films and TV and stories that seem to have a direct line to truth. Characters and situations that, whether straight-dramatic or genre-fanciful, are grounded in a recognisable form of human behaviour and connection; ones that don't seem like they're acting in service of the plot, or genre conventions, or posing for the trailer. This is what has always appealed to me about the films of the 1970s -- a decade in which indie dramas, absurd exploitation films and studio comedies all seemed to reflect an unvarnished, tangible, authentic quality. This is terrain writer-director Kenneth Lonergan understands. While I was divided on his epic, troublesome drama Margaret from a few years back, his first film, 2000's You Can Count On Me was a little gem, and all three of his films draw upon his extensive background writing and directing for the stage, a background steeped in mining the minutiae of human behaviour, of human frailty. Using small observations of people struggling through enormous personal tragedy, Lonergan teams with his peerless cast to burrow deep into these primal truths. Casey Affleck (we'll set aside his problematic personal life for the purposes of this review) finds another gear in this performance, deeply inhabiting this bereft man, permanently broken and almost unbearably open-nerved with self-immolating guilt. Michelle Williams -- much more at home in such surrounds -- makes a nuclear impact with relatively little screen time, Kyle Chandler is a damn-near angelic presence in this thing and Lucas Hedges is assured and just about perfect, marking him as someone who's career I'll be following from here on in. Rather than wallow in grief -- which, in my truth-seeking state, would utterly repulse me -- Lonergan and his cast know the ebbs and flows of life, the everyday joys and fuck-ups and wins and losses and loads and struggles and dumb baggage and macho bullshit and compromises and passion and indignities and loves and bruises of the whole damn thing. For a film that made me barely suppress howls of tears, Manchester by the Sea also features some of the laugh-out-loud funniest, and most warmly affectionate, moments I saw anywhere -- on film, television or otherwise -- all year. Because that's the way life is. You never see it coming. But when it does, you will be unprepared. It may even destroy you. What Manchester by the Sea shows us is, there is no outcome. There's just getting through life, until it ends. But we've got a hell of a better chance of getting through it together. We just have to have the empathy, and the stamina, to try. With Manchester by the Sea, Kenneth Lonergan has, for me, unquestionably crafted a true American masterpiece. Thank you all so much for reading my annual ramblings, and for supporting us here at Cinema Viscera throughout the year! I want you to know how much it all means to me, and I can't wait to return the favour by showing you our film next year... and the one after that. Vive le cinema! Paul Anthony Nelson

1 Comment

|

What fresh hell is this?A semi-regular blog exploring films, popular culture, current or future projects and (more often) year-end wrap-up and opinions from CINEMA VISCERA's co-chief, Paul Anthony Nelson. Archives

December 2023

Categories |

Cinema Viscera acknowledges that its offices are on stolen Wurundjeri land of the Kulin Nation, and we pay our respects to Elders past, present and emerging. Sovereignty was never ceded. Cinema Viscera is contributing to the ‘Pay The Rent’ campaign and we encourage others to consider paying the rent with us: https://paytherent.net.au/

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed